What would it mean for an electronic device to know more about your partner's emotional state than you do? Or be capable of predicting a future bout of misery through statistical analysis of accumulated data? When does technology become too invasive?

Happylife explores these issues through the development of emergent real-time dynamic passive profiling techniques applied to mediate and display human emotive states in a family home.

The science

Happylife is the result of an ongoing collaboration with Reyer Zwiggelaar and Bashar Al-Rjoub of Aberystwyth University Computer Science Department.

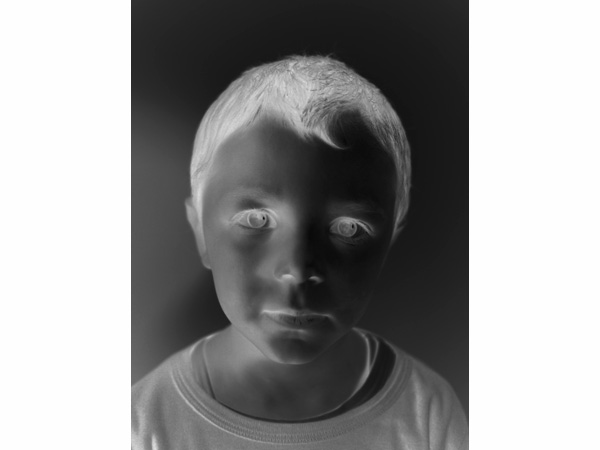

Aberystwyth University’s research is to develop real-time dynamic passive profiling techniques for detecting malicious intent in areas of border control and national security. In practice the thermal image of an individual passing through a control point is captured on entry to secure a datum setting. A computer programme then analyses changes to the live image during a period of questioning, looking for particular patterns of thermal flow that suggest malicious or dubious intent. The thermal camera operates from up to four metres distance, is completely non-invasive and is capable of detecting minute changes in thermal flow.

The technology is currently operational and going through a testing and validation process through controlled user testing studies before being applied in airports across the UK.

The design

The speculation begins by imagining how these advanced sensing technologies and computer algorithms might be deployed in a family home.

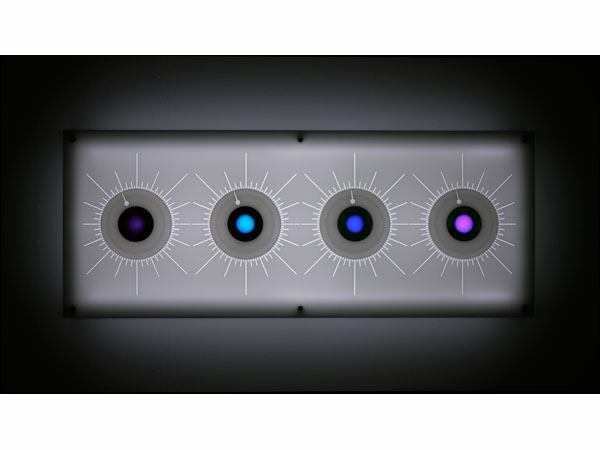

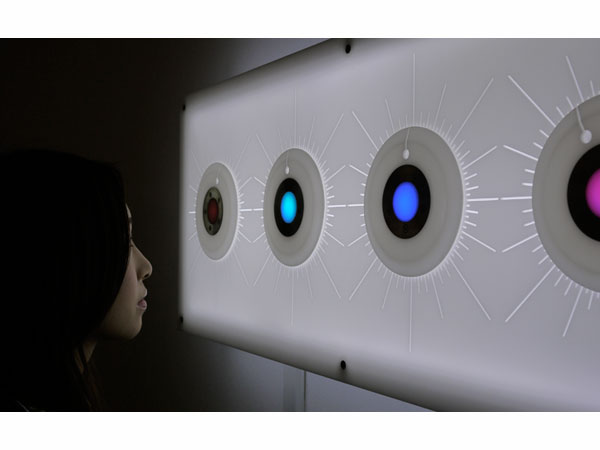

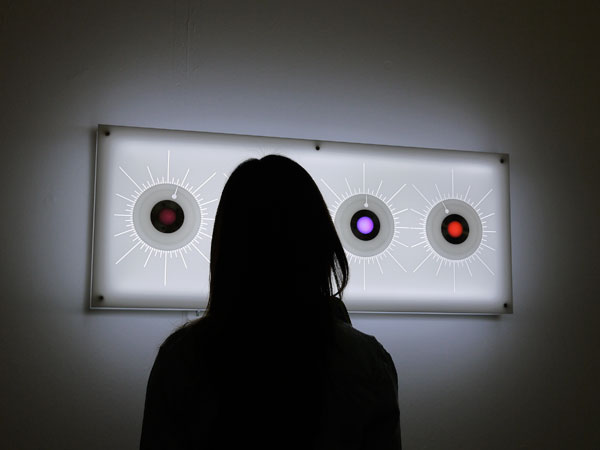

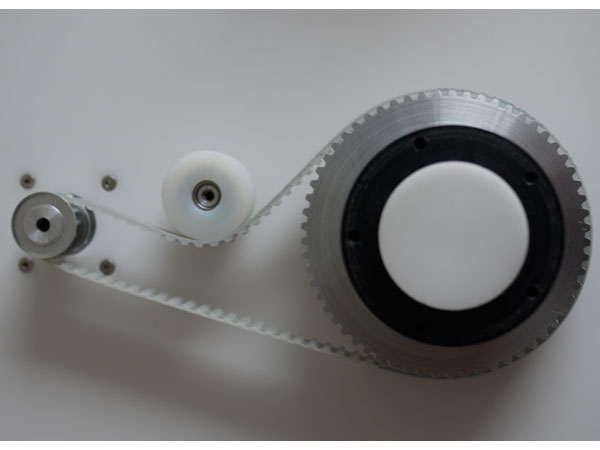

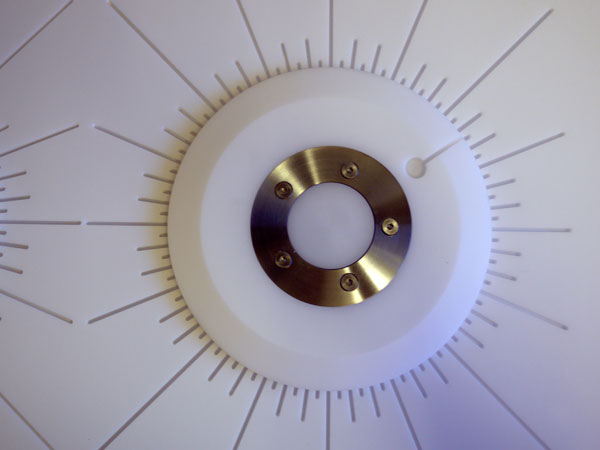

We built a visual display linked to the thermal image camera. The system employs facial recognition software to differentiate between family members. Each personal dial has two pointers; one showing the current state taken from the most recent thermal image capture and one showing the predicted state where the system would expect the dial to be based on the processing of accumulated statistical data.

When dealing with the subject of human mood, an obvious output would have been pointers towards states such as happy or sad; whilst this would have made the project more accessible and sensational, it would have been factually incorrect. We decided on a heavily graduated rotary dial with no literal pointers. This would allow for the user to calibrate the dial over time, generating a more complete and personal understanding of its output.

To fully exploit the narrative potential of the technology, it would be necessary for the device to be operational in a home for some time - allowing for the accumulation of data and its subsequent mining and analysis, and checking for the emergence of patterns or long-term shifts in status, both of which might go unnoticed by the occupants. This plays to the strengths of computer technology and facilitates new forms of interaction with technology.

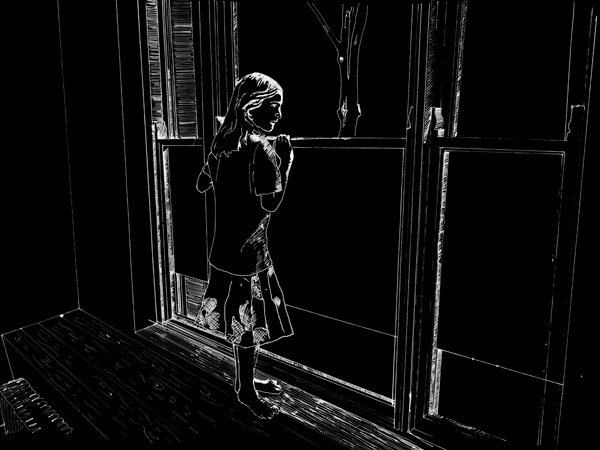

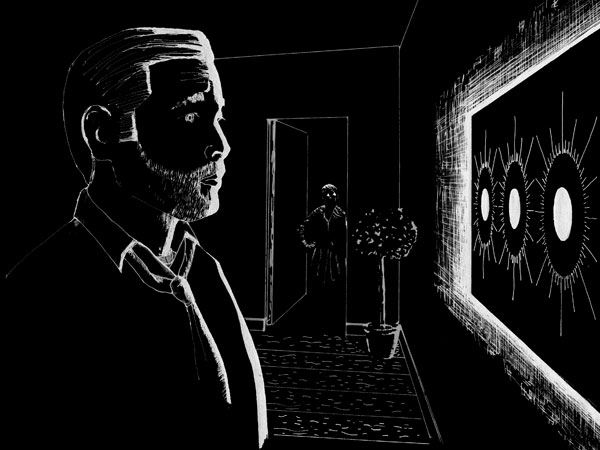

To examine the consequences of Happylife, we speculated on the emotional impact of its deployment in the home of a traditional nuclear family over a 15-year period. These are presented as a series of vignettes, written in collaboration with Dr Richard M. Turley

The context - technology

A glance at the cultural and political landscape into which Aberystwyth University’s research will be applied reveals an increasing use of advanced surveillance technology for purposes of national security. The terrorist attacks in New York, London and elsewhere in the last decade heightened fears around the globe, with the consequence of accelerating the development of security-related technology. In addition to this, the global SARS epidemic in 2003 added a different dimension to the culture of fear, introducing the use of thermal image cameras to check the health of incoming passengers at many Asian airports.

Running parallel to the implementation of technological devices for policing and monitoring is the increasingly popular migration of similar devices into the world of entertainment. One example of this shift is the (pseudo) science of polygraphy. With a history going back over a century, lie detection devices were originally tools used by experts on potential criminals, spies and paedophiles. Although the credibility of lie detection devices has long been in question, their progression into popular culture is almost complete. Lie detectors (often partnered with DNA test results) are a regular feature on daytime reality television programmes, where they are used to mediate family disputes and solve fidelity issues; technology is increasingly seen as an infallible judge of human character.

The context – smart home

An important challenge was for the proposal not to be confused with existing ‘smart’ home concepts. These commonly follow the utopian tradition of labour-saving devices, home automation and technologically implemented notions of comfort. These proposals, though, commonly neglect more complex human factors, ignoring the emotional interactions that take place between family members and friends in the home. More inspirational were the short stories in classic fiction such as the ‘Happylife Home’ in Ray Bradbury’s The Veld and J G Ballard’s ‘Psychotropic House’ in The Thousand Dreams of Stellavista:

“'Maybe I don't have enough to do. Maybe I have time to think too much. Why don't we shut the whole house off for a few days and take a vacation?'

'You mean you want to fry my eggs for me?'

'Yes.' she nodded.

'And darn my socks?'

'Yes.' A frantic watery-eyed nodding.

'And sweep the house?'

'Yes, yes - oh yes!'” (Bradbury, 2008, p.13)

“It's always interesting to watch a psychotropic house try to adjust itself to strangers, particularly those at all guarded or suspicious. The responses vary, a blend of past reactions to negative emotions, the hostility of the previous tenants ... ” (Ballard, 2006, p.415)

Whilst both stories follow the common dystopian science fiction route, they embrace the dynamic complexity of the home environment, introducing technology to mediate and manipulate human emotional experience. The Happylife proposal was designed to sit somewhere between the dystopian worlds of Ballard and Bradbury and the utopian corporate smart home, acknowledging the complexity of domestic human interactions whilst employing near-future informatics technology.

Here is a link to more images on Flickr.

The future

This is an ongoing collaboration. The current prototype is fully functional so the next phase of the project will be to install the camera and display in a family home.

Happylife explores these issues through the development of emergent real-time dynamic passive profiling techniques applied to mediate and display human emotive states in a family home.

The science

Happylife is the result of an ongoing collaboration with Reyer Zwiggelaar and Bashar Al-Rjoub of Aberystwyth University Computer Science Department.

Aberystwyth University’s research is to develop real-time dynamic passive profiling techniques for detecting malicious intent in areas of border control and national security. In practice the thermal image of an individual passing through a control point is captured on entry to secure a datum setting. A computer programme then analyses changes to the live image during a period of questioning, looking for particular patterns of thermal flow that suggest malicious or dubious intent. The thermal camera operates from up to four metres distance, is completely non-invasive and is capable of detecting minute changes in thermal flow.

The technology is currently operational and going through a testing and validation process through controlled user testing studies before being applied in airports across the UK.

The design

The speculation begins by imagining how these advanced sensing technologies and computer algorithms might be deployed in a family home.

We built a visual display linked to the thermal image camera. The system employs facial recognition software to differentiate between family members. Each personal dial has two pointers; one showing the current state taken from the most recent thermal image capture and one showing the predicted state where the system would expect the dial to be based on the processing of accumulated statistical data.

When dealing with the subject of human mood, an obvious output would have been pointers towards states such as happy or sad; whilst this would have made the project more accessible and sensational, it would have been factually incorrect. We decided on a heavily graduated rotary dial with no literal pointers. This would allow for the user to calibrate the dial over time, generating a more complete and personal understanding of its output.

To fully exploit the narrative potential of the technology, it would be necessary for the device to be operational in a home for some time - allowing for the accumulation of data and its subsequent mining and analysis, and checking for the emergence of patterns or long-term shifts in status, both of which might go unnoticed by the occupants. This plays to the strengths of computer technology and facilitates new forms of interaction with technology.

To examine the consequences of Happylife, we speculated on the emotional impact of its deployment in the home of a traditional nuclear family over a 15-year period. These are presented as a series of vignettes, written in collaboration with Dr Richard M. Turley

The context - technology

A glance at the cultural and political landscape into which Aberystwyth University’s research will be applied reveals an increasing use of advanced surveillance technology for purposes of national security. The terrorist attacks in New York, London and elsewhere in the last decade heightened fears around the globe, with the consequence of accelerating the development of security-related technology. In addition to this, the global SARS epidemic in 2003 added a different dimension to the culture of fear, introducing the use of thermal image cameras to check the health of incoming passengers at many Asian airports.

Running parallel to the implementation of technological devices for policing and monitoring is the increasingly popular migration of similar devices into the world of entertainment. One example of this shift is the (pseudo) science of polygraphy. With a history going back over a century, lie detection devices were originally tools used by experts on potential criminals, spies and paedophiles. Although the credibility of lie detection devices has long been in question, their progression into popular culture is almost complete. Lie detectors (often partnered with DNA test results) are a regular feature on daytime reality television programmes, where they are used to mediate family disputes and solve fidelity issues; technology is increasingly seen as an infallible judge of human character.

The context – smart home

An important challenge was for the proposal not to be confused with existing ‘smart’ home concepts. These commonly follow the utopian tradition of labour-saving devices, home automation and technologically implemented notions of comfort. These proposals, though, commonly neglect more complex human factors, ignoring the emotional interactions that take place between family members and friends in the home. More inspirational were the short stories in classic fiction such as the ‘Happylife Home’ in Ray Bradbury’s The Veld and J G Ballard’s ‘Psychotropic House’ in The Thousand Dreams of Stellavista:

“'Maybe I don't have enough to do. Maybe I have time to think too much. Why don't we shut the whole house off for a few days and take a vacation?'

'You mean you want to fry my eggs for me?'

'Yes.' she nodded.

'And darn my socks?'

'Yes.' A frantic watery-eyed nodding.

'And sweep the house?'

'Yes, yes - oh yes!'” (Bradbury, 2008, p.13)

“It's always interesting to watch a psychotropic house try to adjust itself to strangers, particularly those at all guarded or suspicious. The responses vary, a blend of past reactions to negative emotions, the hostility of the previous tenants ... ” (Ballard, 2006, p.415)

Whilst both stories follow the common dystopian science fiction route, they embrace the dynamic complexity of the home environment, introducing technology to mediate and manipulate human emotional experience. The Happylife proposal was designed to sit somewhere between the dystopian worlds of Ballard and Bradbury and the utopian corporate smart home, acknowledging the complexity of domestic human interactions whilst employing near-future informatics technology.

Here is a link to more images on Flickr.

The future

This is an ongoing collaboration. The current prototype is fully functional so the next phase of the project will be to install the camera and display in a family home.