What would robots look and behave like if their designs were not informed by historical and stereotypical representations?

For this project we re-imagined the robot, shifting away from humanoids and pet-like devices towards forms and behaviours more appropriate for the domestic landscape and the complexities of human desire.

Robot adaptation

Directly installing a laboratory robot, or a robot from science fiction into the home would expose it to the rules of domestic life, modern consumer culture and the vagaries of taste and fashion. Research culture and science fiction have their own rules and expectations that define the robot’s form and behaviour, but fundamentally these are very different to those in the home. Carnivorous Domestic Entertainment Robots explores how a robot could be adapted to domestic life – for simplicity this process can be broken down into three areas:

1. Aesthetic adaptation: form follows familiar

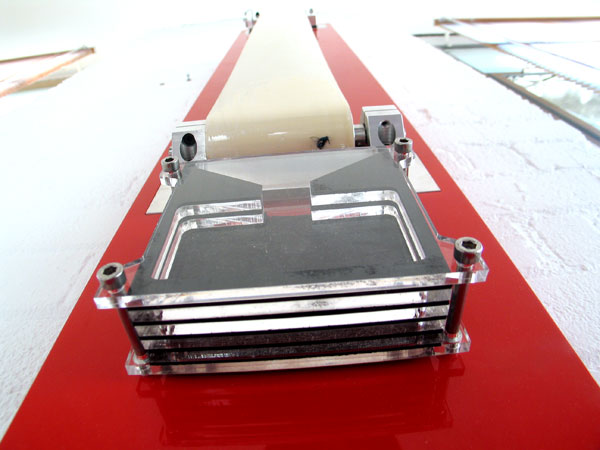

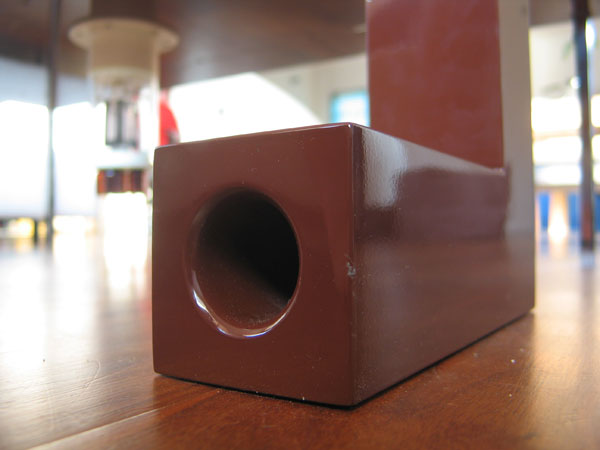

For a robot to comfortably migrate into our homes, appearance is critical. We applied the concept of adaptation to move beyond the functional forms employed in laboratories and the stereotypical fictional forms often applied in the media. In effect creating a clean slate for designing robot form, then looking to the contemporary domestic landscape and the related areas of fashion and trends for inspiration. The result is that on the surface the CDER series more resemble items of contemporary furniture than traditional robots. This is intended to facilitate a seamless transition into the home through aesthetic adaptation.

2. Functional Adaptation

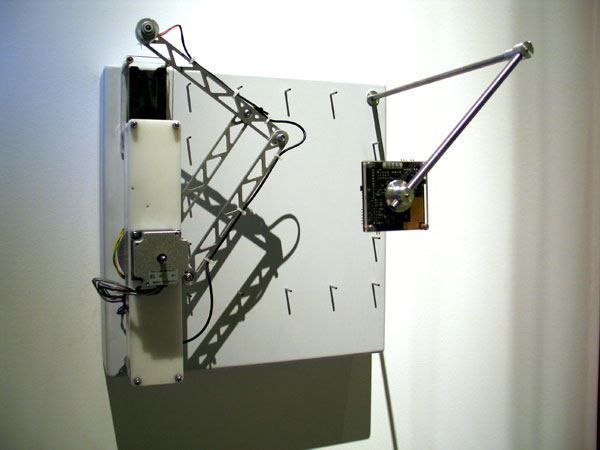

The utilisation of a microbial fuel cell (MFC – see Afterlife project) to provide energy to the robots meant that the utilitarian functions commonly associated with robots would be severely limited by the amount of energy available, this rules out complex mechanical movements or power hunger electronic components.

One of the major themes of contemporary robotic research is the development of artificial companions or entertainment robots. We began to reimagine what engagement with an artificial object could be, coming back to the Frankenstein myth and the notion of artificial life. By exploiting the narrative potential of the fuel cell, specifically the method of providing it with living nourishment, the possibility of energy autonomy and the resulting perceived living artificial entity, we imagined a new category of object existing somewhere between living thing like a pet or houseplant and normal product.

In setting up the dynamic relationship between the owner and the robot we borrowed from well-established techniques in film genres such as horror, thriller and science fiction to provide a spectacle. Susan Sontag describes in her essay on science fiction how the ‘freakish, the ugly and the predatory all converge – and provide a fantasy target for righteous bellicosity to discharge itself, and for the aesthetic enjoyment of suffering and disaster’ (Sontag: essay in Mast and Cohen 1985, p.456). She goes on to state that science fiction films are one of the purest forms of spectacle (Ibid). In our attempt to manufacture a similar experience on the part of the viewer we embellished the predatory technique of the robots, to create a very suspenseful and dramatic aesthetic operation.

The use of living organism as food source also has the advantage of introducing a random aspect to robot function that overcomes their predictability.

3. Interactive adaptation: people/insect/robot interaction

In domesticating the robot it was necessary to apply an appropriate method for the harvesting of food. To enhance the psychological power of the robot we considered it necessary to reduce physical interaction to a minimum, as the autonomous nature of the cell’s activity would be rendered effete by the necessity of human hands to feed it. By referencing predatory techniques of carnivorous plants and applying these methods to the robots it was possible to create logical and low energy techniques for the attraction and capture of prey. Interactions then, are mostly psychological and emotional: in addition to those described above are the qualities of nurture we might experience from caring for pets and houseplants, and the inevitable relationship and fear of death that comes through being responsible for living things.

Like Frankenstein’s monster the CDERs require human assistance to bring them to life, using either mains power or a standard battery to allow their predatory mechanisms to initially operate. Once switched on they begin to accumulate the biomass necessary for the fuel cells to generate electricity. To show their energy status some of the Robots have graphic displays, these may remain unlit for many months or even years but they could turn on at any moment, keeping the owner engaged, just as a fisherman might watch a static float for hours on end in the anticipation that sooner or later it will dip into the water.

The robots are build as five semi-operational prototypes.

But are they robots?

It was essential for the objects to be classifiable as robots. To achieve this we went beyond the basic definition as suggested by the Robot Institute of America (“A re-programmable, multifunctional manipulator designed to move material, parts, tools, or specialized devices through various programmed motions for the performance of a variety of tasks.” (1979)) and aimed to satisfy the more prescriptive criteria recognised by roboticists:

The CDERs are energy autonomous as a consequence of using the microbial fuel cell as energy source.

Their capability, via programming, to capture biomass gives them agency.

They move or have mechanical moving parts.

They can sense their environment.

Each performs a limited utilitarian function.

The Carnivorous Domestic Entertainment Robots being described at the "What If" exhibition, Science Gallery, Trinity College, Dublin:

And recently featured on BBC1: Wallace and Gromit's World of Invention:

For this project we re-imagined the robot, shifting away from humanoids and pet-like devices towards forms and behaviours more appropriate for the domestic landscape and the complexities of human desire.

Robot adaptation

Directly installing a laboratory robot, or a robot from science fiction into the home would expose it to the rules of domestic life, modern consumer culture and the vagaries of taste and fashion. Research culture and science fiction have their own rules and expectations that define the robot’s form and behaviour, but fundamentally these are very different to those in the home. Carnivorous Domestic Entertainment Robots explores how a robot could be adapted to domestic life – for simplicity this process can be broken down into three areas:

1. Aesthetic adaptation: form follows familiar

For a robot to comfortably migrate into our homes, appearance is critical. We applied the concept of adaptation to move beyond the functional forms employed in laboratories and the stereotypical fictional forms often applied in the media. In effect creating a clean slate for designing robot form, then looking to the contemporary domestic landscape and the related areas of fashion and trends for inspiration. The result is that on the surface the CDER series more resemble items of contemporary furniture than traditional robots. This is intended to facilitate a seamless transition into the home through aesthetic adaptation.

2. Functional Adaptation

The utilisation of a microbial fuel cell (MFC – see Afterlife project) to provide energy to the robots meant that the utilitarian functions commonly associated with robots would be severely limited by the amount of energy available, this rules out complex mechanical movements or power hunger electronic components.

One of the major themes of contemporary robotic research is the development of artificial companions or entertainment robots. We began to reimagine what engagement with an artificial object could be, coming back to the Frankenstein myth and the notion of artificial life. By exploiting the narrative potential of the fuel cell, specifically the method of providing it with living nourishment, the possibility of energy autonomy and the resulting perceived living artificial entity, we imagined a new category of object existing somewhere between living thing like a pet or houseplant and normal product.

In setting up the dynamic relationship between the owner and the robot we borrowed from well-established techniques in film genres such as horror, thriller and science fiction to provide a spectacle. Susan Sontag describes in her essay on science fiction how the ‘freakish, the ugly and the predatory all converge – and provide a fantasy target for righteous bellicosity to discharge itself, and for the aesthetic enjoyment of suffering and disaster’ (Sontag: essay in Mast and Cohen 1985, p.456). She goes on to state that science fiction films are one of the purest forms of spectacle (Ibid). In our attempt to manufacture a similar experience on the part of the viewer we embellished the predatory technique of the robots, to create a very suspenseful and dramatic aesthetic operation.

The use of living organism as food source also has the advantage of introducing a random aspect to robot function that overcomes their predictability.

3. Interactive adaptation: people/insect/robot interaction

In domesticating the robot it was necessary to apply an appropriate method for the harvesting of food. To enhance the psychological power of the robot we considered it necessary to reduce physical interaction to a minimum, as the autonomous nature of the cell’s activity would be rendered effete by the necessity of human hands to feed it. By referencing predatory techniques of carnivorous plants and applying these methods to the robots it was possible to create logical and low energy techniques for the attraction and capture of prey. Interactions then, are mostly psychological and emotional: in addition to those described above are the qualities of nurture we might experience from caring for pets and houseplants, and the inevitable relationship and fear of death that comes through being responsible for living things.

Like Frankenstein’s monster the CDERs require human assistance to bring them to life, using either mains power or a standard battery to allow their predatory mechanisms to initially operate. Once switched on they begin to accumulate the biomass necessary for the fuel cells to generate electricity. To show their energy status some of the Robots have graphic displays, these may remain unlit for many months or even years but they could turn on at any moment, keeping the owner engaged, just as a fisherman might watch a static float for hours on end in the anticipation that sooner or later it will dip into the water.

The robots are build as five semi-operational prototypes.

Carnivorous Domestic Entertainment Robots from Auger-Loizeau on Vimeo.

But are they robots?

It was essential for the objects to be classifiable as robots. To achieve this we went beyond the basic definition as suggested by the Robot Institute of America (“A re-programmable, multifunctional manipulator designed to move material, parts, tools, or specialized devices through various programmed motions for the performance of a variety of tasks.” (1979)) and aimed to satisfy the more prescriptive criteria recognised by roboticists:

The CDERs are energy autonomous as a consequence of using the microbial fuel cell as energy source.

Their capability, via programming, to capture biomass gives them agency.

They move or have mechanical moving parts.

They can sense their environment.

Each performs a limited utilitarian function.

The Carnivorous Domestic Entertainment Robots being described at the "What If" exhibition, Science Gallery, Trinity College, Dublin:

And recently featured on BBC1: Wallace and Gromit's World of Invention: