This project explores the human experiential potential of the sense of smell, applying contemporary scientific research in a range of domestic and social contexts.

The current low status of smell is a result of the revaluation of the senses by philosophers and scientists of the 18th and 19th centuries. Smell was considered lower order, primitive, savage and bestial. Smell is the one sense where control is lost, each intake of breath sends loaded air molecules over the receptors in the nose and in turn potentially gutteral, uncensored information to the brain.

At the same time our bodies are emitting, loading the air around us and effecting others in ways we are only now starting to understand.

Momentum has recently been gathering in smell related research. Scientists, after a century long hiatus, have started to realize the importance of the olfactory sense and its complex role in many human interactions and experiences. For the purposes of this project, the key areas have been outlined below:

Dating and genetic compatibility

For the Amazonian Desana marriage is only allowed between individuals with different odours. (same with Batek Negrito of the Malay Peninsula). In conjunction western research (wedekind et al, 1995. Proc R London ser B 260:245-249) has proven that Humans use body odour to identify genetically appropriate mates.

These facts highlight the current situation in western culture; many olfactory experiences occur in the subconcious and therefore have little affect on our concious decision making process. The Desana behaviour proves that humans do have the ability to identify different human smells but in relatively recent times we have either forgotten how to use it or chosen to mask the body's natural smell with perfumes and deodorant.

Health

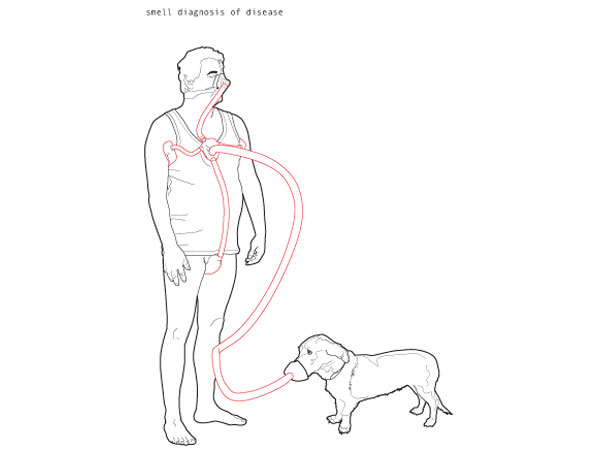

Hippocrates (4th Century BC) first suggested that illness could be diagnosed through smell emissions (body odour). Avicenna (10th Century AD) used urine to detect maladies. Recently dogs have been used to locate cancerous cells in the human body.

A cat residing in a home for the elderly correctly identified those members close to death by lying next to them during the final hours.

Smell and health are clearly closely related but the devaluation of the olfactory sense has left smell diagnosis in the same category as leech therapies and lunchtime frontal lobe lobotomies.

Wellbeing

This area is closely related to health but could be viewed as

1. The personal reaction to smell input (incoming olfactory information) rather than emissions from the body.

Scent marketers and sensory branding utilize the close relationship between smell and emotion to create positive sensory consumer experiences directly related to a specific brand.

An experiment at a U.S casino showed that by releasing a pleasant odour into the atmosphere, takings rose by up to 40%.

2. Controlled or chosen emissions leaving the human body. This takes into account the role of deodorant and perfume. Research has shown that due to the overuse of chemicals as a means of aromatizing the body, some Americans have lost touch with their personal identity. (Synnott and Howes) With the result that we are reduced to visual means for defining the sense of self.

Cooking

The rise of molecular gastronomy (the science of cooking) has highlighted some of the roles of smell in both the process of cooking and taste experience. A recent episode of Heston Blumenthal's 'In search of perfection' highlighted new sensory possibilities in the consumption of the black forest Gateaux. One ingredient (kirsch) was removed from the cooking process to be sprayed into the atmosphere during consumption.

The Maillard reaction plays an important role in the creation of flavours and aromas.

Each type of food has a very distinctive set of flavor compounds that are formed during the Maillard reaction. It is these same compounds that flavour scientists have used over the years to create artificial flavors. As many as six hundred components have been identified in the aroma of beef.

The future

The initial impetus for the project came from a 2006 article in the New Scientist magazine featuring research being done at Florida State University. By targeted deletion of the Kv 1.3 channel gene super smelling mice with altered glomeruli were created. Their smell was enhanced by anything from 1000 - 10000 times in sensitivity. Humans have the same gene so the hypothetical question was could we enhance our own sense of smell in the same way.

There is also a large amount of contemporary research being done on digital noses - technology that can record, store and emit smells. The potential for products with olfactory capabilities is obviously huge.

Methodology

The aim of the project is apply contemporary scientific research and by utilising the medium of design, develop new consumer experiences and services. Scientific knowledge can struggle to break free from the confines of academia; communicating findings to a wider public audience and generating discussions as to what kind of society their technologies could potentially facilitate.

Design has the potential to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and user (public) understanding. The language of products and their behaviour is universal. The utilitarian aspect of design offers a space where technology can meet its public audience.

This space can be speculative, a testing ground for ideas and possibilities, utopias and dystopias or pragmatic, offering real opportunities for new human experiences.

Design proposal

The first issue was to identify the potential problems and issues posed by the sense of smell. Predominantly due to its animalistic nature and our lack of control over its application.

To this end smells have been separated into two categories:

1. Smells emanating from the body (smell output)

2. smells arriving at the body (smell input)

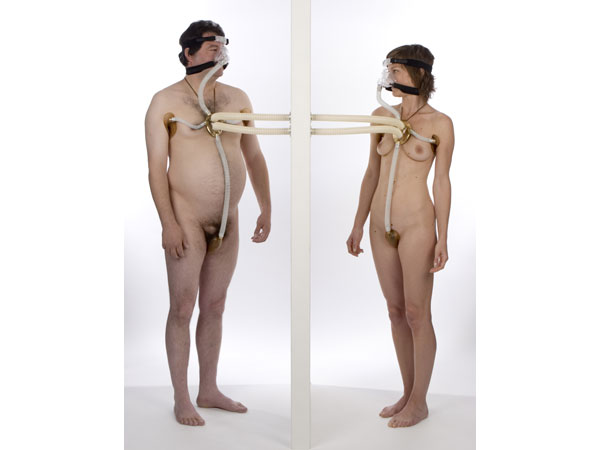

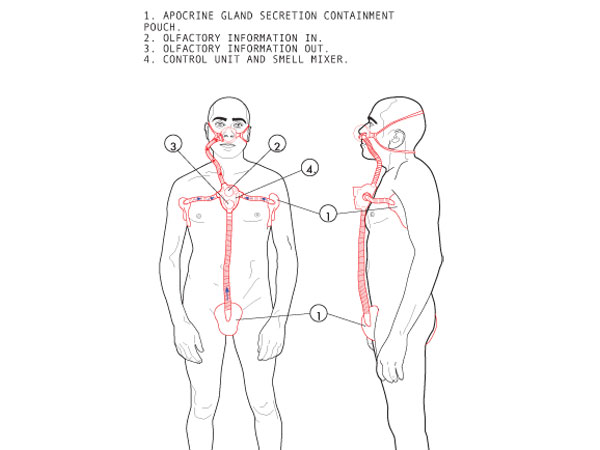

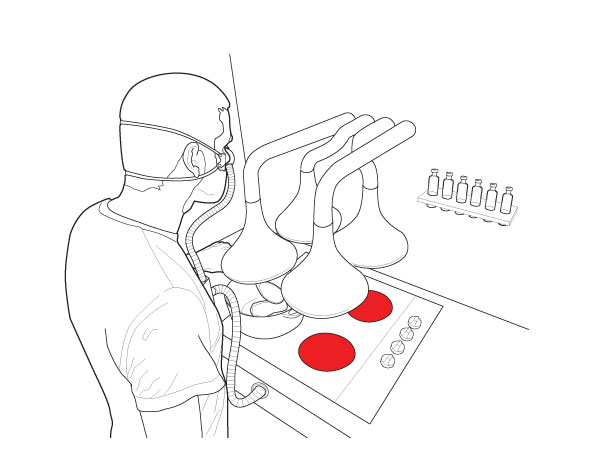

To facilitate control over both these variables the smellsuit has been devised. Sealed pouches encapsulate the apocrine glands (scent glands containing pheromones) preventing oxidation (which creates unpleasant body odours) and channeling smells to the chest mounted control unit. All input smells also arrive here allowing the wearer to have the choice of which smell to concentrate on.

The suit functions on several levels:

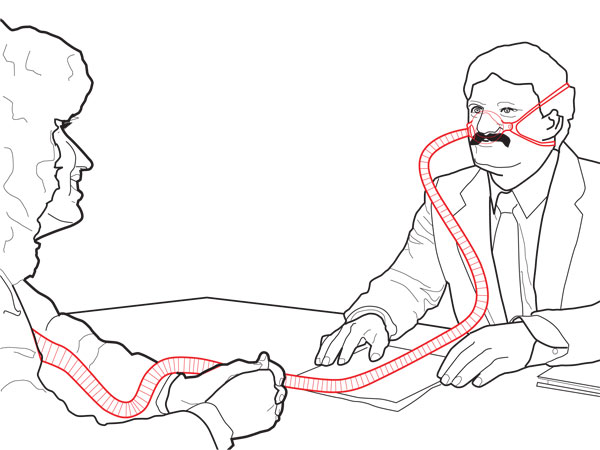

1. Psychologically it sanitises the act of smelling. The chest mounted control unit separates the smell reception from its source, effectively isolating the olfactory from the visual.

2. It offers physical control over both smell input and output.

3. Its operation allows it to be utilised in various contexts facilitating new smell-based experiences.

4. Its visual form allows it to act as a messenger for the project, communicating the concept through more normative media. (when the olfactory experience is not applicable)

The smell suit also has a pseudo scent input for smell training and calibration. Hypothetically artificial scents could be created to calibrate the olfactory experience in the same way that tuning forks calibrate the auditory and pantone charts are used with colour.

Current status

The smell suit prototype has been built to a semi-functional level. This has so far been used for photographic scenario generation (on a continuing basis):

1. Smelling oneself. Addressing the loss of personal identity through use of deodorants and a necessary preliminary process for the smell blind date.

2. The smell blind date (or the apocrine gland transfer system). This concept is based on the olfactory genetic selection research outlined above.

Smell+ being described at the "What If" exhibition, Science Gallery, Trinity College, Dublin:

The current low status of smell is a result of the revaluation of the senses by philosophers and scientists of the 18th and 19th centuries. Smell was considered lower order, primitive, savage and bestial. Smell is the one sense where control is lost, each intake of breath sends loaded air molecules over the receptors in the nose and in turn potentially gutteral, uncensored information to the brain.

At the same time our bodies are emitting, loading the air around us and effecting others in ways we are only now starting to understand.

Momentum has recently been gathering in smell related research. Scientists, after a century long hiatus, have started to realize the importance of the olfactory sense and its complex role in many human interactions and experiences. For the purposes of this project, the key areas have been outlined below:

Dating and genetic compatibility

For the Amazonian Desana marriage is only allowed between individuals with different odours. (same with Batek Negrito of the Malay Peninsula). In conjunction western research (wedekind et al, 1995. Proc R London ser B 260:245-249) has proven that Humans use body odour to identify genetically appropriate mates.

These facts highlight the current situation in western culture; many olfactory experiences occur in the subconcious and therefore have little affect on our concious decision making process. The Desana behaviour proves that humans do have the ability to identify different human smells but in relatively recent times we have either forgotten how to use it or chosen to mask the body's natural smell with perfumes and deodorant.

Health

Hippocrates (4th Century BC) first suggested that illness could be diagnosed through smell emissions (body odour). Avicenna (10th Century AD) used urine to detect maladies. Recently dogs have been used to locate cancerous cells in the human body.

A cat residing in a home for the elderly correctly identified those members close to death by lying next to them during the final hours.

Smell and health are clearly closely related but the devaluation of the olfactory sense has left smell diagnosis in the same category as leech therapies and lunchtime frontal lobe lobotomies.

Wellbeing

This area is closely related to health but could be viewed as

1. The personal reaction to smell input (incoming olfactory information) rather than emissions from the body.

Scent marketers and sensory branding utilize the close relationship between smell and emotion to create positive sensory consumer experiences directly related to a specific brand.

An experiment at a U.S casino showed that by releasing a pleasant odour into the atmosphere, takings rose by up to 40%.

2. Controlled or chosen emissions leaving the human body. This takes into account the role of deodorant and perfume. Research has shown that due to the overuse of chemicals as a means of aromatizing the body, some Americans have lost touch with their personal identity. (Synnott and Howes) With the result that we are reduced to visual means for defining the sense of self.

Cooking

The rise of molecular gastronomy (the science of cooking) has highlighted some of the roles of smell in both the process of cooking and taste experience. A recent episode of Heston Blumenthal's 'In search of perfection' highlighted new sensory possibilities in the consumption of the black forest Gateaux. One ingredient (kirsch) was removed from the cooking process to be sprayed into the atmosphere during consumption.

The Maillard reaction plays an important role in the creation of flavours and aromas.

Each type of food has a very distinctive set of flavor compounds that are formed during the Maillard reaction. It is these same compounds that flavour scientists have used over the years to create artificial flavors. As many as six hundred components have been identified in the aroma of beef.

The future

The initial impetus for the project came from a 2006 article in the New Scientist magazine featuring research being done at Florida State University. By targeted deletion of the Kv 1.3 channel gene super smelling mice with altered glomeruli were created. Their smell was enhanced by anything from 1000 - 10000 times in sensitivity. Humans have the same gene so the hypothetical question was could we enhance our own sense of smell in the same way.

There is also a large amount of contemporary research being done on digital noses - technology that can record, store and emit smells. The potential for products with olfactory capabilities is obviously huge.

Methodology

The aim of the project is apply contemporary scientific research and by utilising the medium of design, develop new consumer experiences and services. Scientific knowledge can struggle to break free from the confines of academia; communicating findings to a wider public audience and generating discussions as to what kind of society their technologies could potentially facilitate.

Design has the potential to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and user (public) understanding. The language of products and their behaviour is universal. The utilitarian aspect of design offers a space where technology can meet its public audience.

This space can be speculative, a testing ground for ideas and possibilities, utopias and dystopias or pragmatic, offering real opportunities for new human experiences.

Design proposal

The first issue was to identify the potential problems and issues posed by the sense of smell. Predominantly due to its animalistic nature and our lack of control over its application.

To this end smells have been separated into two categories:

1. Smells emanating from the body (smell output)

2. smells arriving at the body (smell input)

To facilitate control over both these variables the smellsuit has been devised. Sealed pouches encapsulate the apocrine glands (scent glands containing pheromones) preventing oxidation (which creates unpleasant body odours) and channeling smells to the chest mounted control unit. All input smells also arrive here allowing the wearer to have the choice of which smell to concentrate on.

The suit functions on several levels:

1. Psychologically it sanitises the act of smelling. The chest mounted control unit separates the smell reception from its source, effectively isolating the olfactory from the visual.

2. It offers physical control over both smell input and output.

3. Its operation allows it to be utilised in various contexts facilitating new smell-based experiences.

4. Its visual form allows it to act as a messenger for the project, communicating the concept through more normative media. (when the olfactory experience is not applicable)

The smell suit also has a pseudo scent input for smell training and calibration. Hypothetically artificial scents could be created to calibrate the olfactory experience in the same way that tuning forks calibrate the auditory and pantone charts are used with colour.

Current status

The smell suit prototype has been built to a semi-functional level. This has so far been used for photographic scenario generation (on a continuing basis):

1. Smelling oneself. Addressing the loss of personal identity through use of deodorants and a necessary preliminary process for the smell blind date.

2. The smell blind date (or the apocrine gland transfer system). This concept is based on the olfactory genetic selection research outlined above.

Smell+ being described at the "What If" exhibition, Science Gallery, Trinity College, Dublin: